Dear friends,

After almost 30 years, I picked up Candide ou L’Optimisme (Candid or Optimism) written by the 18th century French philosopher and Enlightenment thinker Voltaire, with its most notable and somewhat mysterious quote singing in my head, “We must cultivate our garden”.

The last time I studied this text in the 1990s, I was a young impressionable student of French literature in Mumbai, India. I was tickled by its droll names and side-splitting scenes of satire—Voltaire’s trademark—not to mention its nail-biting Arabian Nights-like storytelling, with Candide hopping from one country to another in a series of bawdy misadventures. Candide is essentially a larger-than-life coming-of-age story of the simple-minded namesake protagonist, born illegitimately to Baron Thunder-ten-Tronch (I told you, the names are hilarious), and expelled into the big bad world for kissing the Baron’s daughter Cunegonde, who becomes the object of his indefatigable pursuit across continents.

However, re-reading this story mid-life, I was most struck by the parallels between Candide’s self-realization that we must above all, cultivate our garden, and the calling of karma yoga or the Path of Action in the third chapter of the ancient Indian scripture, the Bhagavad Gita.

The Bhagavad Gita, written around 3100 BCE and attributed to the seer Veda Vyasa, is a manual of practical instructions on how to live an informed life following the principles of the ancient Indian philosophy of Vedanta, mostly concerning the training of our mind. It comprises 18 chapters that are inserted bang into the middle of action in the Indian epic, Mahabharata, as a discourse between Lord Krishna and the warrior Arjuna who does not want to fight in the battle of Kurukshetra, symbolic of our reticence at facing challenges in life.

The crux of the Bhagavad Gita is that actions are not to be avoided. In fact, we must use our actions or our work (karma) to rid ourselves of the constant desires (vasanas) produced by our mind. In Candide’s case, his chief vasana, which becomes his delusive obsession and fuels his trans-continental journey, is his lust for Cunegonde.

The ancient seers saw that humans are the mind, and our world, filled with sense objects, constantly tears our mind apart by blasting it with stimuli, which in turn provoke wants, needs, and desires (think ads and shopping expeditions). It’s only by using actions intelligently that we can exhaust ourselves of our mental dirt or vasana by giving our mind something productive to do. It’s not unlike the adage that an idle mind is a devil’s workshop, and therefore we must keep ourselves busy and informed.

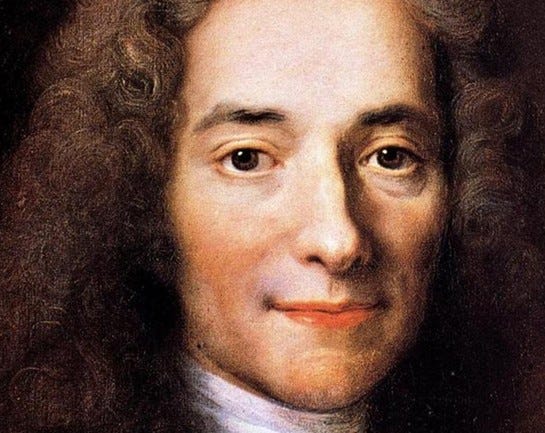

The Gita also informs us that the Path of Action (karma yoga) and the Path of Knowledge (gyana yoga) go hand in hand, and the former is preparation for the latter. That is, our well-chosen actions help us become wiser, and by becoming wiser, our subsequent actions in turn, become more and more informed. It’s when Candide reaches this realization—after his long and arduous journey trekking across continents—that he utters his unforgettable Vedantic words, “We must cultivate our garden.” Voltaire, by the way, was said to have been influenced by the Vedas, ancient religious texts from India that were transcribed in writing between 1500 CE – 500 CE, informing the basis of Hinduism and hence the Bhagavad Gita.

“The Vedas were the most precious gift for which the West had ever been indebted to the East.” Voltaire18th century French philosopher and author of Candide, Jean-Marie Arouet, whose pen name was Voltaire.

Throughout the novella, Candide is fired up by the pursuit of his Cunegonde and this takes him across incredible hardships and miseries—he is terrorized by war, ravished by earthquakes, faces debilitating sickness, and is even imprisoned in the French prison, Bastille. Candide is indeed a man of action but his actions were only informed or rather misinformed by his desire and lust for Cunegonde. In other words, his vasana for Cunegonde was powered by his senses and a volatile and egotistic mind, and not dictated by purity of motive or a spirit of surrender, pre-requisites for the intelligent action of karma yoga.

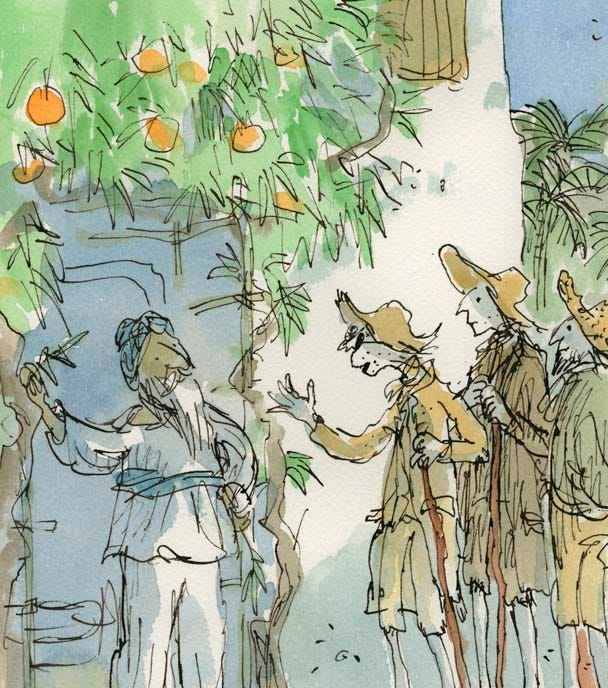

Candide’s botanical epiphany

Then, towards the end of the book, Candide arrives in Constantinople, tired, beat up, and not even sure he wants Cunegonde anymore (incidentally, she also turned ugly over the course of the book, beat up herself by rape and a brutal life). He meets an old Turkish man sitting quietly under the tree, ignorant of even his nation’s affairs. Instead, he simply chooses to tend to the 20-acres of his garden delivering fruit to the city. He invites Candide, Pangloss, and Martin, another philosopher friend who joins them during their journey, to eat fresh fruit from his garden and his children even perfume their beards. Candide remarks to Pangloss that the Turk seems to not only be in a much better place than any of the kings with lavish palaces whom they had met during their voyages, but he seems wiser and content as well.

Through his honesty, simplicity, and repetitiveness of the actions of tending to his garden, the Turkish man not only kept busy, but has acquired peace and wisdom or gyana yoga through his actions or his karma yoga, of cultivating his garden endlessly.

Action and knowledge go hand-in-hand in life.

Thus, the dichotomy in Candide’s mind was resolved. He realizes that it’s the Path of Right Action—namely tending to the small garden of his world—and not preoccupying himself any more with the world’s affairs and galivanting across continents—that he can exhaust his vasanas. This is also precisely the moment when he looks at Pangloss, going a rant about the dangers of grandeur, and states decisively, “We must cultivate our garden”. Enough said, he seems to imply. Wisdom from babbling and stubbornly believing all happens for the best, without any personal action or karma towards the good, is useless and is not going to do him good anymore.

True wisdom comes from action alone.

Illustration of the old Turkish man meeting Candide, Pangloss, and Martin in his garden. Taken from Quentin Blake’s website.

I’ll leave the final word to the Turk, just as Voltaire did in his book: “Our labor (or karma yoga) preserves us from three great evils—weariness, vice, and want.”

Enough said, let’s act and do our karma.

What struggles and pleasures do you have with your own karma? Do share your thoughts.

Meaningfully yours,

Anu

Something along same lines. Karma as simple as making your own bed to start the day .

https://youtu.be/sBAqF00gBGk

I’m finding in my life that whether one’s preference is karma yoga, jnana yoga, bhakti yoga, or dhyana yoga, the more you follow one the more you do all.