It was the last stop on our drive across the spectacular Basque country coastline in northern Spain this February, led by our guide José Luis Ugena, and the only city incidentally, located inland. But anticipation was flying high. I was looking forward to reliving a touchpoint from my former life as a French literature student—Pablo Picasso had immortalized this town in his namesake gut-wrenching painting. For my son, an avid history buff, Guernica was one of his first buzzes in his quiz bowl career kicked off in elementary school—history in action was awaiting him.

Yet, as we entered this infamous Basque town late afternoon, nothing belied the town’s brutal past: fluffy white clouds dotted a clear blue sky; brown wooden balconies neatly hugged cream-colored buildings; and Platano de sombra trees lined up tidily along the lanes, looking like specters raising their arms up to the sky, devoid of their summer leaves. It looked like a middle-class European city—and I don’t mean that as an insult.

Clearly, Guernica had risen from its ashes.

Clean and sleepy are two adjectives I’d associate with the modern town of Guernica. Strange, given its grim past.

Eighty years back, on April 26, 1937, this town of 10,000 citizens became an explosive experiment for Hitler. Upon the behest of an equally devious dictator, Spain’s Francisco Franco, Hitler sent his Luftwaffe to casually bombard the town with one hundred thousand pounds of high-explosive and incendiary bombs to practice his Blitzkrieg doctrine of terror bombing. Within a matter of 4 hours, the town, and its inhabitants—out late afternoon for their weekly Monday market day—were dead, and the town was obliterated. The operation eventually opened the way to Franco's capture of the city of Bilbao during the Spanish Civil War and his victory in northern Spain—his main motivation of course, for the heinous act.

The ruins of Guernica in 1937 after the town was bombed by German aircraft. Photograph: AP

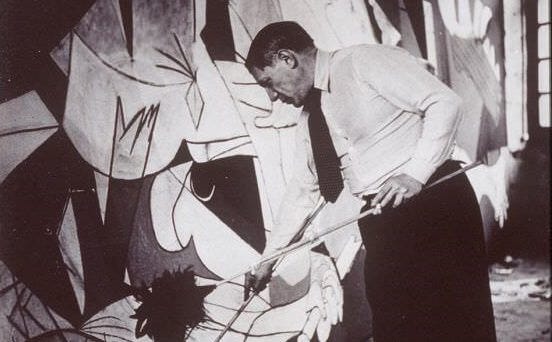

Legend has it that Picasso, at the time of Guernica’s bombing, was living in Paris and had not gone back to his native Spain in a while. But the event, which mainly killed women and children, shook him to the core. When he received the commission to do the painting, he intentionally chose it be devoid of color, except black and white, like the newsprint in which he read the story. He carefully articulated heartbreaking imagery in the painting, revealing the futility of war—a shrieking woman holding a dead baby, a bull representing Franco’s brutality, a disemboweled horse, a mutilated army officer, dismembered arms, and a burning fire. A famous account about the painting goes, while Picasso was living in Nazi-occupied Paris during World War II, one German officer allegedly asked him, upon seeing a photo of Guernica in his apartment, “Did you do that?” and Picasso responded, “No, you did.”

Pablo Picasso working on his Guernica painting (from pablopicasso.org)

Former King of Spain, Juan Carlos, and his wife, Sofia, open the exhibition Pity and Terror, Picasso’s Path to Guernica, at Madrid’s Reina Sofia Museum. Photograph: Succession Picasso/DACS, London 2017. Seeing the painting at the Madrid museum was frankly underwhelming compared to visiting the town and seeing the mural.

While Guernica’s home is the Reina Sofia Museum in Madrid, the town of Guernica boasts of a giant mural of the painting etched on to…the enclosing wall of an apartment complex! Yes, a rather banal milieu for a chef d’oeuvre that captivated the world. My son could not peel his eyes off from the mural, possibly thinking of the all his world history tournaments. And I had to pinch myself—I was standing in the very town that the action in the painting took place—it was as surreal as the style of the painting. However, the town’s residents casually walked past this icon with babies in strollers, kids walked home with backpacks, and right next door, was what looked like an (out-of-place) ultra-luxurious Spanish villa. I experienced a few emotional summersaults—awe at setting foot in the town that inspired Picasso, making the world weep; the strange happenstance of finding a piece of art history so casually strewn onto a random cement wall; and admiration and astonishment at the normalcy of a town that experienced a complicated re-birth in history.

The mural of Guernica in its namesake town casually sprawled on the walls of an apartment complex.

I was mostly moved that Guernica rose from its ashes. That’s a lot of good coming from the bad and the ugly. Yet, I was still searching for the beauty of it all.

Especially after what I saw at the Pasaleku shelter next. I gingerly entered it—it was one of the original bomb shelters remaining in Guernica today. Men, women, and children crammed in here on that terror-filled day. The shelter looked more like a tomb—a small semi-circular tunnel with an arched ceiling, musty smelling, and a sullen gray—the last place you’d want to hang out on a sunny afternoon. On the day of the bombing, we were told the tiny enclave was packed to its brim with wailing children, moms praying or some of whom had fainted, and residents screaming at the shock waves that ensued from each pounding.

The shelter was packed on the day of our tour too, a grim reminder of the town’s vicious past. I had ignored carrying my customary face mask for such indoor activities and I could not get myself to watch the footage of the bombing being filmed on the moist walls, although my son insisted with his newly-minted teen view of the world, that it was “just history”. Intentionally seeking out the barbaric imperfections of history, even in the quest of perfecting my understanding of the world today, was not my forté—I admit to being a bit faint of heart of all things macabre, even in movies (Although, I was a huge fan of visiting cemeteries of French authors and poets during my time as a student in Paris).

I left, relieved that Guernica had risen from its ashes…

The confines of the original Pasaleku bomb shelter were tight as tourists crammed in to experience what it was like to be cordoned off during an aerial raid. An audio of the sirens signaling an aerial raid played constantly to make it more evocative of the D-day.

Arguably, the most important real-life piece of history that survived from the bombing of Guernica was lo and behold, the Gernikako Arbola or the oak tree, which today is located next to the Assembly House of Bizkaia, next on our itinerary (see picture below). Since the bombing, the tree went on to becoming the symbol of perseverance of the Basque people and their ongoing struggles to gain autonomy from Spain, even today. My son was most excited to see the Gernika tree, a fact that had José amused. He explained that most visitors, even ones from other parts of Spain, were not aware of the tree, much less a 7th grader from America!

The current Gernika tree stands within the grounds of the Assembly House of Bizkaia. Symbol of the Basque national pride, much care is taken to ensure that there’s one Gernika tree alive and thriving at all times. The oak tree is depicted on the heraldic arms of Biscay and subsequently on the arms of many of the towns of Biscay.

Why the Gernika tree? For centuries, the ancient oak tree in Guernica sheltered the Lords of the Bizkaia—the province of Spain that is historical territory of the Basque Country. These leaders met in the shade of this tree to discuss important issues concerning the region. It’s kind of like how the Athenians met on the hill as my son explains in this video about the Gernika tree. The first Gernika tree called the “father tree” was planted 450 years back and the second one planted in 1742—what they call the “old tree”—survived the bombing of Guernica, a cutting of which still stands enclosed (see picture below) on the grounds of the Assembly House of Bizkaia. A total of five Gernika trees have been planted so far, with the most recent one (seen in the picture above) being age 14, planted in 2015. So precious is this oak tree that the gardeners of the Biscayan government keep several spare trees grown from the tree's acorns ready to take a spot if the current tree dies or is God forbid, destroyed.

The "old tree" (1742–1892), re-planted in 1811. The trunk now is located in a special enclosed area on the lawns of the Assembly House.

Clearly, the tree is well taken care of, and the Basque people take pride in it.

José explains, “The Tree of Gernika is for me, an element that symbolizes the history and traditions of the Basque people. It reminds me that, not so long ago, we had our own laws, sports, and customs. The tree represents the future too, always respecting others but being proud of ourselves. The oak is one of the strongest trees, just like the Basques.”

Granted, Guernica cannot boast of the spectacular beauty of its neighboring coastal towns—Mundaka, Spain’s surfing capital, or Bermeo, the largest fishing town in the area. Guernica’s beauty lies in its tale of survival and its complex and nuanced history and character: it is death, survival, destruction, rebirth and the pride and tenacity of the Basques—all rolled into one, an imperfectly perfect beauty. In that sense, it’s like any of us going through life, a mix of good and bad, evolving and metamorphosing constantly, plowing through and not giving up.

What is one thing or place you experienced that is as nuanced or hard to capture as Guernica? It could be a person too. Sometimes in life, there are people as well who are multifaceted and imperfectly perfect. You love them and hate them at the same time. Do share your thoughts in the comments box below.

Meaningfully yours,

Anu

PS: History buffs, check out this April 29, 1937 newspaper article on the bombing of Guernica from the frontlines, from The Guardian.

PPS: Learn more about Jose’s tour company, Bizkaia Maite Tours.

Learning so much history through your writings . Maybe some day will visit . History and literature were my two most favorite subjects growing up. Even managed to clinch a few tough European history it’s AC questions from Rohan in mock practice ( with Sahil though I have no chance ).