Dear friends,

I share the second of my favorite poems this week in honor of the National Poetry Month. Chanson d’automne (Song of autumn) by the 19th century French symbolist poet, Paul Verlaine, had me so captivated in the early 1990s as a student of French literature, that I calligraphed, painted, and framed it, and it has occupied a special place in my study since. That such poetic beauty can be born from despair is a testament to life being imperfectly perfect.

The cheerful yellow color, the swirl of the leaves, and the cadence of the poem make me feel happy, although the content of the poem itself is ironically, sad.

Chanson d’automne, loosely translated, goes like this. Alas, the poem does lose its original flavor and musicality, in translation. You can listen to a recitation of the original French poem here.

With long sobs

The violins

Of autumn

Wound my heart

With languorous

Monotony.

All choking

And pale, when

The hour sounds,

I remember

Departed days

And I weep;

And I go

Where ill winds blow,

Buffeted

To and from,

Like a

Dead leaf.

Translation © Richard Stokes, from A French Song Companion (Oxford, 2000).

A song disguised as a poem

The unforgettable quality of Chanson d’automne, composed in 1866, comes from its built-in musicality and cadence, both of which are brilliantly depicted in this poem. Talk about form reflecting content in perfect harmony.

In fact, years later, Verlaine writes in L’ Art Poétique that poetry was above all, music.

Music first and foremost, and forever!

Let your verse be what goes soaring, sighing,

Set free, fleeing from the soul gone flying

Off to other skies and loves, wherever.

His verses in Chanson d’automne indeed set your soul flying right away by their musicality, when he introduces the image of a violin in the first stanza. It makes you imagine someone is playing the poem to you on the instrument. Verlaine also brings in the repetitive syllabic sound of the letter “l” and its breezy musicality engulfs you right away:

Les sanglots longs

Des violons

De l'automne

Blessent mon cœur

D'une langueur

Monotone.

In the poem, Verlaine shares how the autumn landscape makes him feel sad. It reminds him so much of his past that he feels as torn apart as one of the leaves falling off the tree to the ground in autumn. Clearly, fall is not his season! He explains how the plucking or the “sobs” (les sanglots) of the violin playing, wounds his heart with a languorous monotony. It’s almost as if the violin itself is playing the verses, wrapping you in its musicality as Verlaine the poet writes the poem for the audience.

No wonder, the poem is called the song of autumn.

Riding high and low like an autumnal leaf

The cadence of the poem’s verses become increasingly choppy and short towards the end, mimicking the shaky descent of the falling autumn leaves, the subject of the poem. Here again, the structure of the poem reflects its content. So, the poem “falls” towards the end as much as the dead leaves to the ground in autumn. Note the words “deça, delà” in the last stanza which mean “here and there” evoking the image of a weightless leaf swaying mindlessly to the earth.

Et je m'en vais

Au vent mauvais

Qui m'emporte

Deçà, delà,

Pareil à la

Feuille morte.

The poem closes dramatically with the words feuille morte or dead leaf, almost depicting a jump to death. While cautious not to make too many analogies between an author’s life and his works, Verlaine’s life was also marked by highs and lows like the landscape he paints in the poem, especially in the later years, when he was plagued by alcoholism, affairs, drug addiction, and poverty. His life featured many scandals, one of which was leaving his wife Mathilde—who was only seventeen at the time they married—and their son to have an affair with poet Arthur Rimbaud, quitting France to travel through Europe only to land up firing shots at him in a drunken rage.

Despite its sadness, the swift cadence and shortness of Chanson d’automne has always had me swaying and feeling perky. I guess I am in a happy place when I see it. I don’t know what that says about me—I was in my teens when I first heard it from one of my professors who did such a great job sensitizing us to its musical structure that the form stuck more than the content, I guess.

The D-Day connection

Now here’s an interesting tidbit for the history buffs. Verses from Chanson d’automne were used to send messages to the French Resistance about the timing of the forthcoming invasion of Normandy. In preparation for Operation Overlord, the BBC had signaled to the French Resistance that the opening lines of the Chanson d’Automne were to indicate the start of D-Day operations.

The first three lines of the poem, broadcast on June 1, 1944, “Les sanglots longs / des violons / de l’automne”, meant that Operation Overlord was to start within two weeks. The next set of lines, “Blessent mon coeur / d’une langueur / monotone” meant that it would start within 48 hours and that the resistance should begin sabotage operations on the French railroad system. These lines were broadcast on June 5, at 23:15. Listen here at 1:22 to the original broadcast.

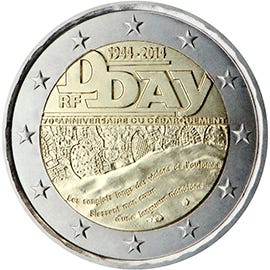

In 2014, in celebration of the 70th anniversary of D-day, France created a €2 coin to commemorate this event. The coin shows the first two lines of this poem and the waves of the sea, symbolic of the Normandy beaches where the Allied forces landed.

And as such, Chanson d’automne changed the course of World War II or the world itself, forever.

So, there’s Chanson d’automne by Verlaine. I hope you enjoyed this introduction to Verlaine—if he is new to you—and this simple, yet beautiful creation of poetry.

Meaningfully yours,

Anu

PS: Here’s another poem I shared earlier this week, in case you missed it. That’s two this week in honor of the National Poetry Month, although I wish I could write and share many, many more!

Amazing. I memorized this poem to recite in French poetry class two decades ago and you reminded me again how beautiful it is! I had forgotten all about it. Merci pour ce beau souvenir....